If we are to believe futurist Thomas Frey, drones will become the most disruptive technology in human history. To be fair Frey’s definition of a drone is more than the flying Unmanned Aerial Vehicles or UAV’s we typically think of when we talk of drones. The reality is though that drones are more than just flying cameras, they’re being used to deliver goods, fight climate change, monitor reefs, supply humanitarian aid, and take part in races.

My involvement with drones is via the statewide VCMP project which uses them to monitor coastal erosion hotspots. “The Victorian Coastal Monitoring Program aims to provide communities with information on coastal condition, change, hazards, and the expected longer-term impacts associated with climate change that will support decision making and adaptation planning.”

As a citizen scientist I’m part of a local team that uses a Phantom 4 drone, aeropoint satellite based markers and some pretty clever software that lets us measure the amount of sand that is shifted along sections of a beach. We do this by overflying sections of the local coast at around two monthly intervals and then crunch the data with the Australian Propellor software. This software allows users to draw virtual transects or plots along or across the beach to compare data across a range of dates. From this we can calculate the amount of sand movement and/or changes in the beach profile amongst other information. The software also enables users to render 3D representations of the beach.

In order to participate in the program we had to undertake some basic training in using the drone safely and efficiently. Whilst not a full remote pilots licence the training did cover off on most of the practical aspects required to get licence certification. We were also made aware of and have to comply with the Civil Aviation Safety Authorities, CASA, rules for flying sub-2kg drones.

Prior to becoming involved in this program I had purchased a couple of small entry level drones with a view to investigating if and where drones might fit within the school curriculum. Since that time a number of things have happened which have sharpened this focus.

The two major consumer drone manufacturers, DJI and Parrot have realised that the education sector is a market that could be tapped into. As a consequence both companies have adapted previous entry level models to better reflect the needs of schools. At the same time educators around the world have also been developing specialised drone options with students in mind. Most of the skills involved in learning to safely fly these entry level drones can also be applied to more sophisticated models, flying a continuous and even figure eight pattern is just as tricky with my Parrot mambo as it is with my Mavic Pro.

Both DJI and Mambo are developing some excellent support materials aimed specifically at the education market. Some major third party developers including Swift Playgrounds amongst others are also developing learning options. Importantly a number of these third party supports originate in Australia and are designing and providing content that fits the Australian Curriculum.

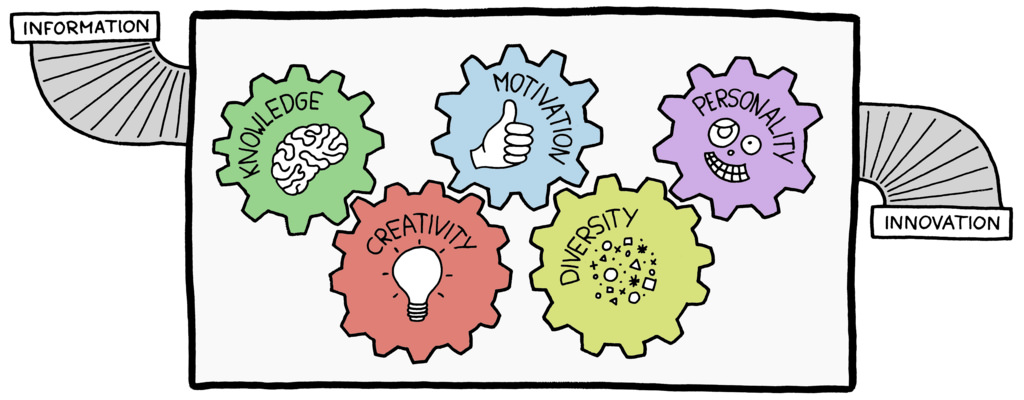

Drones provide a very practical means to develop STEAM projects. In order to best utilize drones it is important to understand the physics of flight and the various systems that combine to keep drones airborne. Designing and making drones fits perfectly within a STEAM framework bringing together science understanding within a design process that involves multiple systems. In addition to basic design work, drone kits provide the opportunity to devise, prototype and test novel uses for drones. The process of constructing drones, (and sometimes flying drones), often involves quite a lot of “trial and error” learning which provides a perfect context for building resilience and learning from failure. Even the best pilots have at least one malfunction.

The better entry level drones come with simple in-built cameras which can be employed to capture images that can be used as evidence of mission completion or as data for analysis. More sophisticated drones can be used in data gathering across the curriculum especially in geography, geology and the natural environment. LEGO connectors on entry level drones enable the addition of lightweight components which can be used to simulate real world missions. In the real world, drones are now also being used to take the place of fireworks and other lighting effects, again something that is within the scope of the classroom.

Another drone component worth considering is an FPV, or first person view camera. When paired with goggles these cameras provides students with an entree to the exciting world of drone racing and open up the many maths based explorations that are involved in this activity. Whilst flying a drone race can be full of thrills, designing courses that are challenging but realistic can be just as exciting.

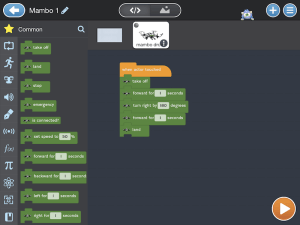

A number of the entry level drones can also be controlled using code from block based through to Python and Arduino. This opens up the opportunity for students to devise, program and fly missions that mimic real world applications. If students are working with more sophisticated drones there are a number of software options available to plan and run missions. Whether using smartphones, controllers or software, flying and coding drones can be quite different to doing similar tasks using terrestrial based vehicles.

Of course with any new technology there is a cost involved and other considerations to take account of. Flying time is one of these; some entry level models typically provide 8-10 minutes of air time per 30 minute charge. With the better options users can purchase combos that have multiple batteries and spare propellers. With micro drones it’s important to understand the control range after which the drone may ‘get lost’. When looking at larger drones it’s important to consider the camera capability as well as navigation features such as collision avoidance and return to base features.

Overlaying all of these consideration is that drones are becoming increasingly available; some are available for as little as $20 from popular stores such as K-Mart. Micro-drones that fit into the palm of your hand can be purchased online again for very minimal cost. Despite the fact that these products contain flyers and instructions on safe and responsible drone use, experience suggests that these are often ignored. Schools offer an opportunity for a more structured review of these rules. Working with drones in schools also provides an opportunity to discuss and consider privacy and other issues associated with drones. Schools also provides a context for learning safe procedures; most damage to drones occurs not in flight but in packing, unpacking and transport.

Having hands-on experience with even entry level drones enables students to better consider options for the use of drones in the wider world. It can also lead to senior level students undertaking certificate level qualifications and even RePL, (remote pilot licences) as is already happening in a number of settings.

Come and meet me at the Leading a Digital School Conference where I will be facilitating hands-0n workshops around Droning in the Classroom, Augmented and Virtual Reality, Engineering Robots, Coding and Data.