One of the problems we have in education at the moment is that the curriculum in some areas is developing so rapidly that parents and the wider community have trouble keeping up. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the STEM subjects area. Where once we created electrical circuits using alkaline batteries, bulbs in bulb holders and wires, current students might be using coin batteries, LED’s, conductive tape or small modular components that connect together via magnets to complete similar and at times more complex tasks.

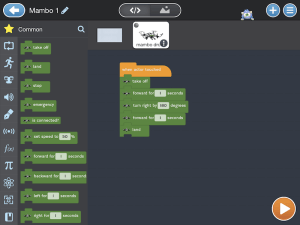

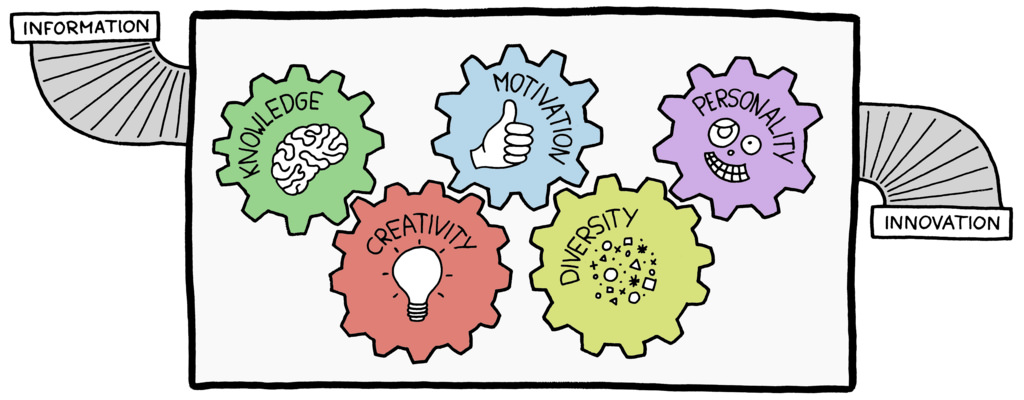

For most parents, technology and engineering were simply not part of their school curriculum. Whilst they may have since learned how to use computers and other devices, the Digital Technologies curriculum advocates that simply using a tool is a very base level skill. Instead the curriculum advocates that students need to learn “how to use technologies to create innovative solutions that meet current and future needs.” To do this students need to understand and use computational thinking. Understanding digital systems and importantly how data and information can be used within these systems is a key to being able to create such innovative solutions.

Teaching approaches are evolving too. In the not too distant past the Science and Maths curriculum was often built primarily around content that could be tested and assessed as known or unknown. Whilst knowledge is still an important component of these subjects process skills as highlighted above, creative use of such skills are now seen as just as important.

The whole notion of STEM or STEAM is also a novelty to many parents more used to notions of discipline based or homogeneous work practices. That a scientist now uses digital componentry more often than a test tube or beaker can be quite revelatory. Understanding how easily data can be captured and not only analysed but used for both ‘good and evil’ can be almost mind blowing.

One of the fun ways to address issues surrounding STEAM is via a family engagement program based on the popular Family Science or Maths programs. Though there are a number of models for running these programs the common feature is a parent, (or other significant adult), working alongside a student on an open ended activity. In some cases programs are run after school, in other variants activities are distributed as a task to be worked on by a parent and child at home together, (note this alternative should not be seen as homework).

The best Family STEAM activities are as open ended as possible but should be capable of being ‘completed’ in a short amount of time. They need to be hands-on and minds-on. If the task is also counter-intuitive then that is even better. In most cases program participants will move through a number of activities which may highlight specific features, eg different aspects of a particular curriculum or principles which underpin practice. This highlights an important caveat, it is important to point out that the activities used in Family STEAM events aren’t how the whole curriculum will or should manifest itself in the classroom. The best STEAM activities involve real problems that are multi-faceted requiring a process approach over an extended period of time and which may not necessarily result in a ‘positive’ outcome. Even the best organised Family STEAM event can’t hope to cover all this detail.

I have had the pleasure to have been involved in a number of Family STEAM events ranging from science based programs through events focussed specifically on technology and more. As a result I have sourced numerous activities that can be readily used to run a program or series of events. These include introductory activities that require minimal instruction or materials such as the following.

In addition to these ‘starters’ programs usually include longer form activities such as Blast Off. Typically these require a facilitator that can be another teacher or an interested parent or community volunteer. Such activities should run for 15-20 minutes. Ideally the activity leader will have tried the activity before the event and also be prepared with some further challenges in mind. In the example below you might ask participants who have a ‘working model” how they might modify it to make the plane go further or whether it is possible to make the plane do tricks. Alternatively participants might be asked to make suggestions for modifications or games that might involve the planes.

In the case of many activities the question of how or why things work is often raised. Some leaders like to include explanations of the science or technology behind their allotted activity. I often prefer to leave things as a question that is open during the event but which can be researched and reported on later in class.

Where possible I have always encouraged the teachers of students involved in the event, (as well as some of the support staff such as librarians and art teachers etc), to be the facilitators for the program. Generally this means that they only have to ‘learn’ one activity that may be repeated a number of times during the event. I’ve found that doing this can serve as great professional development for teachers, who are unsure of aspects of the curriculum and/or the approaches used to teach STEAM.

As suggested earlier Family STEAM events can be a powerful addition to a school program. Whilst they may take time to organise and facilitate, in my experience the benefits always outweigh any cost in time and materials. In addition to the benefits listed above such events can be used to showcase how school science programs can be hands-on and inquiry-based and fun and educational at the same time. Where teachers are used as facilitators the events also provide an opportunity for they and parents to interact in a relaxed situation. Students also gain a sense of community outside school hours.

Most importantly Family STEAM events encourage and foster interaction between parents and children in a non-judgmental space as they enjoy fun educational experiences together, not just doing homework. Parents and students get to see that science is all around us, is achievable and is FUN.

I’m conducting a range of workshops at the Leading a Digital School Conference that map to the Digital Technologies Curriculum. Come along and join me.